What’s the difference between a goal, an objective and a tactic?

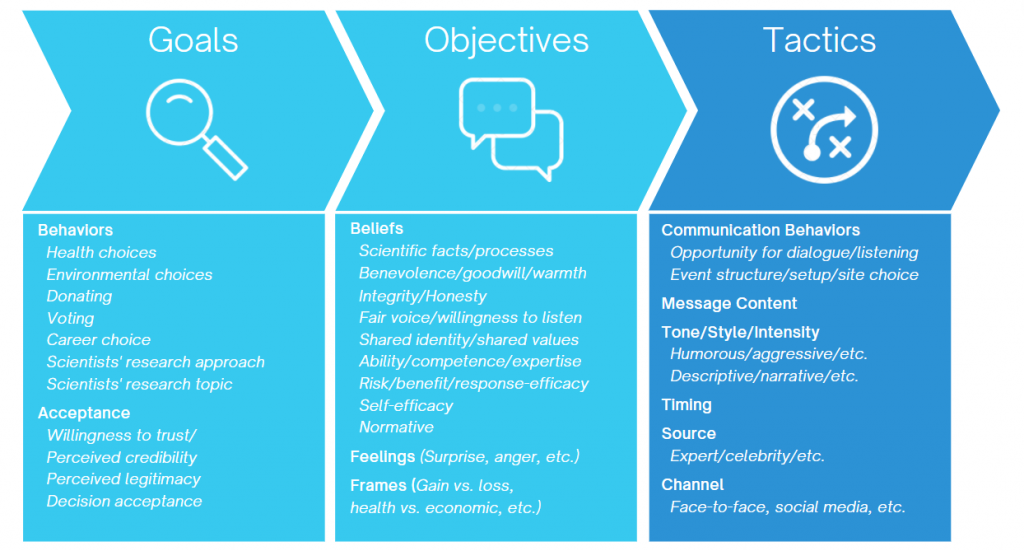

The exact terminology isn’t as important as the underlying concepts. For us, goals are behaviors that you want someone to do, or not do. Perhaps confusingly, trust, can be understood as a behavior from this perspective when it involves the behavior of making oneself vulnerable to the decisions or expertise of a person or organization. This might include accepting decisions as legitimate even if you’re uncertain about the decisions or disagree with the decisions.

Scientists can—and should—also prioritize goal associated with changing their own behaviors, including behaviors about their research topics and methods. Goal behaviors are almost always the outcome of multiple factors.

Unlike goals, we understand communication objectives as being discrete beliefs, feelings, and frames that might result from exposure and attention to specific information or experiences. We often distinguish between beliefs about the natural and physical world from evaluative beliefs about either the trustworthiness of other people and beliefs about behaviors.

Trustworthiness perceptions might include beliefs about benevolence, integrity, voice, identity, or ability. Perceptions about behaviors include beliefs about risks and benefits, beliefs about other peoples’ beliefs (i.e., normative beliefs), and beliefs about oneself and our ability to do a behavior (i.e., self-efficacy beliefs.

Beyond beliefs, communicators can also communicate with the hope of affecting feelings in the form of discrete emotions (e.g., anger, disgust, joy) or how people frame an issue or behavior.

Although we often don’t talk about it directly as an objective, communication choices can also affect the degree and nature cognitive processing (i.e., attention) that people put towards their environment. In this space, the primary objective we think many science communicators want to engender is ‘engagement,’ a concept described below.

Tactics, for us, represent the ground-level communication choices that we all have to make about our behaviors, words, style/tone, and timing of communication. It might also include choices about who communicates and the channel for that communication.

Why do you talk about science communication and not public engagement?

We often use the term ‘engagement’ but do so in a very specific way. For us, engagement activities are science communication activities that are meant to work by ensuring all participants (including scientists) are motivated and able to attend to the information being shared, including information related to other participants and themselves.

In the language of ‘dual process models’ of cognition, this means communication meant to work through ‘system 2,’ ‘systematic,’ or ‘central’ routes rather than cognitive shortcuts as described by ‘system 1,’ ‘heuristic,’ or ‘peripheral’ routes.

We emphasize designing communication that holds participants’ attention because that’s what it takes to change peoples’ beliefs and behaviors over the long term. We have little interest in simply ‘nudging’ people to support science in the short-term and we suspect most scientists feel a similar way. These communication tactics have their place and can be done ethically, but they’re not our primary focus.

Practically, this means we do not want to just use subtle cues such as body language or color to put people in temporary moods or a specific turn-of-phrase to get people to report support on a survey. Instead, we want communicators to explicitly devote time to sharing information specifically related to potential objectives such as risks and benefits, norms, self-efficacy, and trustworthiness beliefs.

How does your research advance diversity, equity, and inclusion?

The behaviors that lead to diversity, equity, and inclusion are all potential communication goals.

For example, it would be perfectly reasonable for a scientist to say that their goal is to try to make sure that more minority scientists choose to pursue administrative roles or that women scientists voice their opinions when making societal decisions. DEI won’t just happen, we need to prioritize these types of goals and pursue strategies involving relevant objectives through ethical tactics

Similarly, diversity, equity, and inclusion effort are also essential tactics, both for ethical and practical reasons. Wise researchers know that building and supporting a diverse team, equitable distribution of benefits, and inclusive spaces makes it possible to achieve a range of desirable objectives, and ultimately goals.

If you want different types of people to believe they’re heard, then it’s important to hear them. If you want people to believe you share their values, then it helps to show that you share their values. If you want a range of beneficial ideas, then you need to hear from people with a range of experiences. Communication isn’t just about messages and style; it’s about behavior.

Our ultimate hope is that our ideas about strategy can help science communicators with DEI goals to achieve success efficientlyl

What about two-way dialogue?

Dialogue can be a powerful tactic but it’s not a goal or communication objective, unto itself.* The closest thing to ‘dialogue’ as an objective in our approach are beliefs/perceptions about others’ willingness-to-listen (i.e., procedural fairness as voice).

We think dialogue is a useful tactic because it has the potential to motivate dialogue participants to pay attention (i.e., “engage”, see above) and increases the likelihood that participants will communicate in ways that allow their dialogue partners to understand what they are saying (i.e., motivation and ability to process).

That being said, the effects of dialogue still depend what people say and do during dialogue. Participants in dialogue can share information related to the full range of beliefs, feelings, and frames.

Also, it is important to recognize that we mean ALL participants. Members of the scientific community who participate in meaningful, symmetrical, two-way dialogue should also be eager to update their beliefs, feelings, and frames when communicating with others.

(*The amount of dialogue could be a meaningful indicator for process evaluation.)

What about storytelling?

Telling stories and ensuring clear and compelling narratives can be tactically effective as one way to help people maintain attention (i.e., cognitive engagement) and as a mechanism to share information about both people and content. It’s hard to have a compelling without people, after all and many science stories put scientists in the role of being helpful and smart.

However, as with dialogue, the context of the stories/narrative also matters. Telling a story that makes scientists seem disconnected isn’t likely to help demonstrate that scientists care about communities, for example.

What about jargon?

Using jargon isn’t inherently bad at a tactic. It’s possible to imagine a situation in which a scientist uses jargon to demonstrate expertise to a specific audience. However, it’s hard to maintain attention (i.e., cognitive engagement) if people can’t follow what you’re saying or writing. There’s more to communication, however, than being clear and vivid.

Clarity and vivid descriptions about the wrong things, however, seems unlikely to advance the interests of the scientific community.

What about misinformation and disinformation?

We understand misinformation as incorrect information that someone shares. A person who purposefully shares misinformation is engaged in disinformation.

The two key questions for us are: Incorrect information about what; and what is the information you want people to know? In this regard, we prefer to focus on fostering the beliefs that we want people to share rather than emphasizing incorrect beliefs.

We also think it matters whether the focus is on information that might be expected to foster trustworthiness beliefs (e.g., competence beliefs, integrity beliefs), or information that pertains to risks and benefits, what others think is normal (i.e., normative beliefs), and what people think about their own capacity to do a behavior (i.e., self-efficacy beliefs).

What about uncertainty?

We have often been asked whether we should include uncertainty as a communication objective. Our view is that someone can be uncertain about any of the beliefs we include as potential communication objectives. For example, it is possible to be uncertain about a scientists’ integrity as well as whether a behavior is risky or beneficials.

Scientists also sometimes tell us they worry that communicating uncertainty will hurt how they’re perceived. Our view is that this largely a moral question rather than a strategic question. If a scientist feels there’s uncertainty, they need to share it and not worry about how that will make them look.

Of course, how much effort to put into communicating uncertainty can present challenges but there’s no reason to think that it would be okay to hide genuine uncertainty. In general, the research does not suggest that communicating uncertainty will hurt trustworthiness perceptions.

What if my ‘goal’ is just to help people love science as much as me?

It’s great to want people to love something you love, especially when that thing is as helpful as science. But why do you want people to love science as much as you? What do you think would be different in the world if they loved science as much as you? The answers to those questions get you closer to a concrete goal.

In general, like us, our sense is that many science communicators have the goal of wanting other people in society to turn to science—and scientists—when faced with challenging problems. And that’s great. You can build strategy on that goal, although it’ll be harder to evaluate. Specificity makes it easier to see (and evaluate) progress, but the underlying concepts remain similar.

What if I don’t know my exact goal?

If feasible, ask for help. A primary role of communication professionals is to help people identify their goals. Strategic communication isn’t meant to be easy.

More generally, however, it’s okay to have start with broad goals and then develop more specific goals as you get more experienced or when opportunities present themselves. When in doubt, it also likely makes even sense to make your goal building trusting relationships with potential stakeholders, including learning what others think and how they think.

The hope is that, in time, you’ll identify goals that you can justify putting resources towards and that supports real needs in real communities.

How do I pick communication objectives?

This is what we think people should mean when they encourage communicators to “know your audience.”

It’s not enough to just know demographics. Ideally, you know something about what your interlocutors believe and feel about your topic of concern and that you have a sense of how they frame the underlying issue. By knowing this, you start to identify potential areas where additional communication can make a difference.

For example, if someone already thinks smoking is bad, it doesn’t make sense to communicate additional information about the risks of smoking. Instead, you might see if it makes sense to emphasize the benefits of quitting or try to help people believe they have the ability to quit (i.e., increase self-efficacy).

Similarly, if you want to ensure behavioral trust by ensuring that people see you as trustworthy then you may want to know whether people see you as competent (i.e., ability), caring (i.e., benevolent), and honest (integrity). Many scientists are already seen as quite competent, and it may therefore make sense to focus on taking steps to bolster communication around perceived motive and integrity (assuming you’re doing things that make you deserving of such perceptions).

These examples also point to the importance of setting communication objectives that involve learning about others’ beliefs, feelings, and framing. If you don’t know how others are seeing the world, you may want to focus your efforts on building your understanding of others’ perspectives.